The French, inexorably judgmental in so many things, are merciful when it comes to the transition from one year to the next. You have until the end of January to send holiday greetings, well wishes, and fond regards.

The French, inexorably judgmental in so many things, are merciful when it comes to the transition from one year to the next. You have until the end of January to send holiday greetings, well wishes, and fond regards.

Today I’m going to use that extension to reminisce about 2017.

I sure did a lot of talking about classic movies last year. I yapped about my favorite classics on Periscope. I rambled about obscure classics like Letty Lynton and Spectre of the Rose and got quoted in Newsweek. I went on a tangent about the cultural cachet of classic films and their lack of availability and made it into the L.A. Times. And to my enduring dream-come-true amazement, I recorded a commentary track for Olive Films’ Blu-ray of Orson Welles’s The Stranger.

But was I writing about classic movies? Nope. Not as much as I would’ve liked. I guess I was too busy watching a lot of new (old) movies that delighted me, scared me, and generally “gave me all the feels.” (As a millennial, I’m contractually obligated to say that.) Interestingly enough, a major theme that unites many of these very different discoveries is radical life changes—journeys from frustration to fulfillment, from cowardice to courage, from conformity to freedom.

So, before I turn the page on 2017, I wanted to compose my thoughts on a few favorite new-to-me films.

The Four Feathers (Merian C. Cooper, Lothar Mendes, and Ernest B. Schoedsack, 1929)

What’s it about? The son of a British general decides to quit the army rather than risk his life to quell an uprising in Sudan. Branded a coward by his comrades and rejected by his fiancée, our hero sets off to rescue his friends and prove his courage.

Why do I love it? It’s always exciting to watch a performance so good that it makes you change your mind about an actor. In this case, who knew that Richard Arlen could be so charismatic? Certainly not me, despite having seen a significant slice of his prime Paramount filmography. His odd combination of boyish swagger and aggrieved aloofness finds its ideal vehicle in this oft-adapted adventure yarn.

Sweat and grime suited Arlen. The image that will stay with me most from this film isn’t shifting sands or fierce tribes or Victorian ballrooms, but a close-up of Arlen at the moment when he puts his body on the line to block mutinous troops from escape. His nostrils flared, his ridiculous cheekbones bulging under rakish stubble, his eyes glittering with defiance, his face leaves an unshakeable impression. I can think of few close-ups that pack the same transformative weight in a character’s arc. At that moment, Arlen’s huge face on the screen of the Capitol Theater became less a face than an emblem for a less disillusioned world. Or the dream of one, because 1929 was pretty damn disillusioning.

Make no mistake, this is heady imperialist propaganda, so rousingly made by masters of the exotic epic Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack that you’ve got to handle it with care. If The Four Feathers extols a bygone way of thinking that we should not mourn, it also exemplifies the sophistication and lost grandeur of the late silent era. And that we should mourn. We can learn a lot from the past, if only how to make a sprawling, monumental, novelistic movie that clocks in at 81 minutes.

Where can you see it? It’s not on DVD, but you can watch a not terrible quality version on the Internet Archive.

The Countess of Monte Cristo (Karl Freund, 1934)

What’s it about? When her fiancé breaks off their engagement, a bit part actress snaps, drives off the set, and arrives at a swanky hotel in in her studio-owned car and glad rags. In a kind of fugue state, she decides to live it up and pass herself off as a Countess. But how long can she keep up the charade? Will new men in her life, a suave aristocrat and a crotchety crook, reveal her secret?

Why do I love it? If The Countess of Monte Cristo is poor man’s Lubitsch, it’s still very rich indeed. Great cameraman-turned-director Karl Freund gives this Great Depression wish fulfillment romp a buoyant frothiness. When I remember this movie, I see contrast between the dire gloom of the early scenes and the cheerful, gilded, 5-star-hotel sparkle of Wray’s sort-of-accidental foray into grand larceny. And don’t get me started on the snowy brightness and snuggly fireside crackle of the romantic subplot. We get a montage of Fay Wray and Paul Lukas frolicking through an alpine paradise of sports and snow in fur coats and designed woolens, for crying out loud.

Though remembered most for her signature scream, Wray was a smart, tough cookie in real life, and The Countess of Monte Cristo gave her the chance to carry a movie (which she did more often than she’s given credit for). She could wrap the audience around her little finger, even when she’s not pursued by a giant ape. Never forget it.

Paul Lukas is dreamier than I ever remember him being. He looks damn fine when smoking in hotel hallways, and Freund lets Lukas smolder frequently. As Wray’s accomplice and gal pal (who apparently shares a bath with her sometimes), Patsy Kelly delivers the lion’s share of funniness. And, as the curmudgeonly master thief who uses Mitzi as bait, Reginald Owen steals plenty of scenes, memorably sneering, “I’m not diabolical. I’m debonair.” What’s not to love?

Where can you see it? Nowhere at the moment. Of all my 2017 discoveries, this is the one I’d most like to rewatch. Unfortunately, it’s buried deep in the archives at Universal. At Capitolfest, I was part of the first audience to see The Countess of Monte Cristo since the initial release. Maybe it’ll show up at a rare film festival near you!

Alexander Nevsky (Sergei Eisenstein, 1938)

What’s it about? A medieval Russian prince leads an army of lusty singing peasants and lovelorn landowners to battle evil baby-burning German invaders.

Why do I love it? Prince Alexander has great hair. Love me some progressive medieval chieftains who fight alongside women, violently dislike religious fanatics, accessorize with blingy medallions, and flip their fabulous, shiny locks victoriously in front of the camera.

Seriously, though, like everybody else who took a college film course (or 9), I had to watch and read a heaping helping of Sergei Eisenstein. It kind of wore thin on me. YES, MONTAGE IS LIKE A HAIKU IN THAT A MEANING IS PRODUCED WHICH IS NOT PRESENT IN A SINGLE IMAGE ALONE. THANK YOU, SERGEI. YOU ARE VERY CLEVER. I left school without any inclination to further explore his work recreationally.

As much as I respect Eisenstein as a film pioneer, I had given up on enjoying any of his films until I saw this rip-roaring action epic. It’s ultimately about beating the living bejeezus out of proto-Nazis. (And in case you have any doubts that the villains are in fact supposed to stand for Nazis, take a good look at what the zealot bishop has on his little hat.)

Eisenstein’s use of black and white and every shade of gray in between packs a punch into each frame. The frigid, dead whiteness of the German knights’ tunics. The masses of dark troops organizing like some macabre ballet on the ice. Prince Alexander and his lieutenants in chainmail, surveying the land from jagged gunmetal cliffs and harmonizing against the silvery sky. (Sure, it didn’t hurt that I saw this on nitrate at the Nitrate Picture Show.)

Despite some deeply disturbing scenes, Alexander Nevsky is exuberantly entertaining. I call it the Eisenstein Capades, maybe the most fun you can have with the father of montage.

Where can you see it? It’s in the Criterion Collection. You can stream it on FilmStruck. Praise be.

Lady in the Dark (Mitchell Leisen, 1944)

What’s it about? Magazine editor Liza Elliott is a Woman Who Has It All. So why can’t she make up her mind—about her upcoming magazine issue, about the men in her life, about what she really wants? Why does she feel listless and depressed? And why have her dreams turned into bizarre Technicolor allegories? Hm, I wonder if it has to do with some kind of Freudian childhood trauma…

Why do I love it? The colors. My lord, the electrifying, terrifying, soul-nourishing, phantasmagoric colors. Blue dresses and red sequins and orange lipstick and neon pink columns surrounded by lavender mists. Busby Berkeley himself would have to call this movie seriously trippy. I’ve seen a lot of movies, and Lady in the Dark must be one of the most visually stimulating films I’ve ever seen. Director Mitchell Leisen explained his philosophy of color as an embrace of dissonance, like the conflicting colors of dresses at a real-life dinner party.

With Lady in the Dark, Leisen creates a film that seems to be rebelling against itself and subjects its surface dogma to a brutal bombardment of destabilizing beauty. The regressive 1940s-ness the script clashes with the liberating fantasia of the images, celebrating the heroine’s spectacularly troubled unconscious, Freudian complexes and all.

I hope to write more about this one in the future, because it’s been haunting me since I left the the screening at TCMFF! Oh, did I mention I saw it on nitrate? I could hardly stay in my seat.

Where can you see it? Not on a legit U.S. DVD. But you can find it on a major online video platform that begins with Y. And some non-legit purveyors of DVDs have it, too.

Cluny Brown (Ernst Lubitsch, 1946)

What’s it about? A maid struggles to fit into her place in society, despite a fascination with plumbing (yes, really!) and her attraction to a refugee writer who cherishes her weirdness.

Why do I love it? As Lubitsch’s penultimate film, Cluny Brown shows a gentler, mellower side of the director’s cheeky comedy, far from the pyrotechnics of his 1930s output. His quiet mastery of the film medium imparts a cozy glow to this wondrous journey of self-acceptance—but you can’t miss the sharp side-eye cast at the nonsensical constraints of convention. (The villains of the piece are grim and instantly recognizable as every self-loathing petty buzzkill sadist you’ve known in your life.)

The chemistry between Jennifer Jones (never spunkier) and Charles Boyer (never more lovable) sings the truth at the heart of Lubitsch’s best work: we’re at our most ridiculously sexy when we’re at our most ridiculous. Get you a man who beams with admiration when you pull out a wrench to bang on drainage pipes or when you drop the dinner tray shrieking about nuts to the squirrels.

Where can you see it? Cluny Brown occasionally airs on TCM. Heaven knows why it’s not available on a legit U.S. DVD, but that’s my excuse for taking so long to see it. You can probably find it on the vast tangle of internets.

The Man I Love (Raoul Walsh, 1947)

What’s it about? Blues singer Petey goes home to help out her family in Los Angeles and lands a job in a nightclub. Can she protect her siblings from tough breaks while fending off the slimy advances of her gangster boss?

Why do I love it? Ida Lupino smokes, croons, gets her heartbroken, wears Milo Anderson gowns, and slaps awful men in a musical noir romance ensemble melodrama. What more could I say?

Where can you see it? Bless Warner Archive. Long may they reign over the MOD kingdom.

Kind Lady (John Sturges, 1951)

What’s it about? A charitable dowager takes an interest in a charming, penniless artist… allowing him to invade her home and hold her prisoner. Will he succeed in robbing her of everything she treasures, including her sanity?

Why do I love it? By this point in her career, Ethel Barrymore’s mesmerizing talents were usually confined to supporting roles (see Portrait of Jennie, The Spiral Staircase, Moss Rose). Kind Lady gave her a leading role, and, boy, does she ever rip into it. Even today, there’s a decided dearth of worthy vehicles for women over 60 to share the craft they’ve honed over their distinguished careers. It’s downright revelatory to watch a mid-century gaslighting thriller centered on a mature, romantically unattached woman.

Beneath the impeccable control of an Edwardian lady, Barrymore exudes a potent combination of dread and determination. In one unforgettable scene, she responds to the mockingly grotesque portrait that her captor has painted of her. Though literally tied down and physically powerless, she slices through his attempt to diminish her and affirms her identity and dignity with her voice alone. I get chills just thinking about it!

Although we’re rooting for Queen Ethel, Kind Lady spins a gripping tale from uncomfortable questions of luxury and inequality. The fascination with art and collection adds an aura of decadence and semi-Gothic obsession to this tale. One senses that the villain doesn’t merely want money. He derives a perverse pleasure from seeking to destroy a woman whose taste, fortitude, and compassion confronts him with his own inadequacies as an artist and a human being.

Where can you see it? Huzzah! It’s out on DVD from Warner Archive, along with an earlier film adaptation (which I’ve heard is excellent as well).

Beat the Devil (John Huston, 1953)

What’s it about? Oh, gosh. Let’s just say that a bunch of devious people try to do devious things and fail miserably. Imagine The Maltese Falcon if everybody was stoned and couldn’t get their sh*t together.

Why do I love it? Weirdly enough, I started watching Beat the Devil maybe 10 years ago and turned it off after 15 minutes. It just didn’t click. The transfer was bad. I wanted to take it seriously (Heck, it’s John Huston and Humphrey Bogart!) and the movie would not cooperate.

Seeing it at TCMFF (with a similarly appreciative audience) made me fall in love with this oddball caper and welcome its canny meta humor. Exhibit A: Robert Morley, trying to release his posse from the clutches of an unamused authority figure, says something like, “Well, surely looking at us should show that we’re honest!” Whereupon the camera pans across the grisliest rogue’s gallery you can imagine, culminating in Peter I’ve-Played-a-Lot-of-Serial-Killers Lorre. Dear reader, I howled with laughter.

This one is a roaring good time if you’re in on the joke—the joke being Hollywood’s penchant for twisty heist films and thrillers set in spicy locales. And daffy savant Jennifer Jones is my new spirit animal.

Where can you see it? It’s fallen into the public domain, so you can watch it just about anywhere they’ve got movies. The DVD I have is not great, but I haven’t bought the Blu yet but I plan on doing so.

Blood and Roses (Roger Vadim, 1960)

What’s it about? Glamorous European aristos who go to costume parties and fall hopelessly in love with their cousins and ride horses around their sprawling countryside estates and cry into their pillows over their love for their cousins. Also vampires?

Why do I love it? Despite my love of vampire movies and Technicolor eye candy, I procrastinated this one for many years, expecting something ponderously trashy (bloodsucking Barbarella, basically). I was surprised by the film’s combination of delicate, youthful sensuality and bitter regret. In one dazzling scene, our heroine stares transfixed by a vision of love she can never share, and psychedelic flashes of fireworks play over her fresh face as it hardens into despondency. Vadim reinvents the aesthetics of the Gothic, giving us ancient dances played off records, sleek mid-century décors chilled by unrequited passion, and ruins demolished by the remnants of WWII shells.

One of my favorite art historians, Kenneth Clark, said that the painter Watteau understood the sadness of pleasure better than anybody else. Blood and Roses is rather like a horror film made by Watteau. If it is a horror film at all. Because, in this movie, the supernatural is not an intrusion into the characters’ lives, not an invading other. The divisions between past and present, self and other, living and dead, dreams and reality, are not the reassuring partitions we like to imagine.

I don’t want to give too much away. Suffice to say, this movie is everything I thought it wouldn’t be: subtle, pensive, lingering… and, dare I say, immortal.

Where can you see it? Jeez, I like a lot of not-on-U.S.-DVD movies, huh? This one is not hard to find if you do a Google video search.

The King of Hearts (Philippe de Broca, 1966)

What’s it about? During the bloody final days of World War I, a timid British soldier is ordered to defuse a massive bomb hidden somewhere in a quaint French town. He discovers that all the “normal” residents of town have fled, leaving only the whimsical inmates of the local asylum. Will he save the day? Even if he does, what happens when he has to march away, back to the sausage-grinder of trench warfare?

Why do I love it? Around once a year, I happen upon a film that utterly wrecks me in public. In 2017, The King of Hearts was that movie. When the theater lights came up at TCMFF, black rivulets of teary eyeliner streamed down my cheeks, and my heart swelled with the sublime recognition that cinema hasn’t lost its power to destroy me.

Those labeled as crazy are truly the sanest among us. War is true madness. These aren’t novel ideas. But The King of Hearts’ air of frenetic, carnavalesque melancholy perfectly captures the sadness and muffled horror of living in a world that doesn’t give a damn about your flickering happiness as much as it cares about you killing people you’ve never met.

It’s one of the few movies that’s effectively captured the absurdity and impaled innocence of World War I. And yet I left the theater on a swell of butterfly-fragile hope. Throughout it all, the tender bonds between Alan Bates and Genevieve Bujold and between the cohort of inmates as a whole exalt the life-saving power of love and imagination—the craziest and most beautiful qualities of humanity.

Where can you see it? The price is a bit steep, but it is available on DVD.

Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb (Seth Holt, 1971)

What’s it about? An archaeologist’s daughter feels the pull of an ancient spirit, a powerful sorceress queen who wants to return to the land of the living. And take her vengeance.

Why do I love it? Hammer horror isn’t exactly known for an abundance of complex female characters. Beyond the “blood and boobs” reputation, however, you’ll find quite a few juicy femme fatale roles in the Hammer canon. Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb offered up arguably Hammer’s best role for an actress. Valerie Leon seems poised to be just another likable daughter figure when we begin to see another personality leech into her, a commanding woman with fearsome occult knowledge.

The ambiguity of this Hammer installment intrigues me. The script wrestles with the good-evil duality that many horror movies accept at face value. Is the Queen Tera really a force of darkness, hellbent on destroying the world as we know it? Or is she a brilliant seer, persecuted all those millennia ago by the ruthless patriarchy? Perhaps she’s both, an eternal embodiment of the knife-edge balance between good and evil that sustain the universe as we know it.

I enjoyed the chutzpah with which Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb toys with its audience, trampling all over the reassuring “rules” of who lives and dies in the Hammer universe. And that last shot, a fitting tribute to the horror genre fixation on women’s eyes, has not left my mind since I saw this underrated Hammer gem months ago.

Where can you see it? Yay, this one is on DVD! Glad to end on a positive note. Otherwise you’d have to endure a tirade about film (un)availability.

Other 2017 recaps and best-of lists that I’ve enjoyed:

Horror and winter weather go together in my mind. Whenever a fierce north wind sets my windowpanes rattling and snow engulfs the landscape like some bizarre fungus, I want nothing more than to curl up with a pot of tea and some spooky stories.

Horror and winter weather go together in my mind. Whenever a fierce north wind sets my windowpanes rattling and snow engulfs the landscape like some bizarre fungus, I want nothing more than to curl up with a pot of tea and some spooky stories.

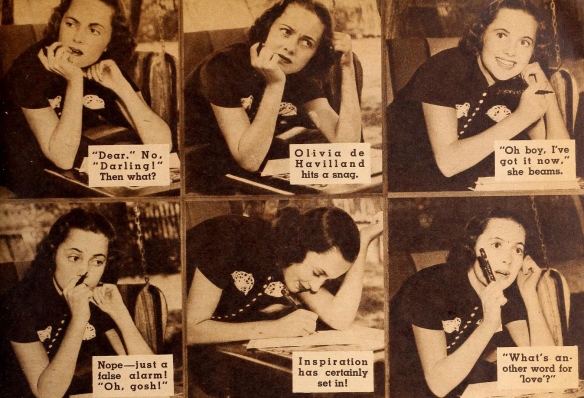

This is the age of Olivia de Havilland. We’re just lucky to be living in it. Today, on July 1, 2016, she turns 100. To celebrate her talent, her courage, and her breathtakingly diverse legacy of screen performances, I embarked on an “Oliviathon” and vowed to watch or rewatch all of her films by the end of this month.

This is the age of Olivia de Havilland. We’re just lucky to be living in it. Today, on July 1, 2016, she turns 100. To celebrate her talent, her courage, and her breathtakingly diverse legacy of screen performances, I embarked on an “Oliviathon” and vowed to watch or rewatch all of her films by the end of this month. After completing a disappointing melodrama called Devotion, Olivia thought she was finished with her constraining Warner Brothers contract. Jack Warner, however, insisted that the time she’d spent on suspension still counted against her. With lawyer Martin Gang, Olivia decided to take Warner Brothers to court for a practice that she considered unlawful. If she lost, she’d never work in Hollywood again.

After completing a disappointing melodrama called Devotion, Olivia thought she was finished with her constraining Warner Brothers contract. Jack Warner, however, insisted that the time she’d spent on suspension still counted against her. With lawyer Martin Gang, Olivia decided to take Warner Brothers to court for a practice that she considered unlawful. If she lost, she’d never work in Hollywood again.

Maybe I did too much living in 2015, because I sure didn’t do much writing!

Maybe I did too much living in 2015, because I sure didn’t do much writing!

Life grants us a limited number of “mothership” moments: raptures of sudden belonging, occasions when our weirdness transforms into an asset, when something beloved and elusive enfolds us.

Life grants us a limited number of “mothership” moments: raptures of sudden belonging, occasions when our weirdness transforms into an asset, when something beloved and elusive enfolds us.

It seems fitting that Gene Tierney should share a “birthday” with Technicolor.

It seems fitting that Gene Tierney should share a “birthday” with Technicolor.

After a dissolve, Ellen is looking in the same bedroom mirror as before—but this time all we see is the reflection, not Ellen. She glides towards the mirror like a phantom and the camera glides in step with her. She dabs perfume on the curve of her neck and retouches her lipstick.

After a dissolve, Ellen is looking in the same bedroom mirror as before—but this time all we see is the reflection, not Ellen. She glides towards the mirror like a phantom and the camera glides in step with her. She dabs perfume on the curve of her neck and retouches her lipstick.