“When I first came here, I believed in justice. I believed that someday I’d be released! Then I began to figure on weeks and months and now I hate the whole world and everyone in it for letting me in for this. Buried in a black filthy hole because I was a good citizen. Because I worked my head off to expose crime—and now I’m a convict. I act like a convict, smell like a convict. I think and hate like a convict!”

“When I first came here, I believed in justice. I believed that someday I’d be released! Then I began to figure on weeks and months and now I hate the whole world and everyone in it for letting me in for this. Buried in a black filthy hole because I was a good citizen. Because I worked my head off to expose crime—and now I’m a convict. I act like a convict, smell like a convict. I think and hate like a convict!”

—Frank Ross (James Cagney)

If you’re looking for a feel-good flick, I wouldn’t recommend William Keighley’s Each Dawn I Die—as the title might suggest. If, on the other hand, you’re seeking one of James Cagney’s most poignant, edgy performances, you came to the right movie.

In this indelibly brutal look at America’s prison system, Cagney plays neither a fearsome gangster nor even a petty hustler, but rather a good guy locked up due to a miscarriage of justice. Crack reporter Frank Ross got a little too close to the corruption he was trying to expose—so the crooked politicians he threatened decided to keep him quiet with a nasty frame-up. Sent to Rocky Point with a twenty-year sentence, Ross forges an unlikely friendship with big shot racketeer Stacey (a sly, swaggering George Raft) who offers to help Ross dig up evidence of his innocence… if Ross helps him escape.

Now, whenever two stars at the top of their game appear in the same movie—receiving equal billing—it’s mighty tempting to see them as competition in a zero-sum contest of “who came off better?” In this case, I applaud how well Each Dawn I Die both stretches and showcases Cagney’s and Raft’s respective talents. Right off the bat, I’ll confess my bias: to my mind Cagney possessed the far greater range as an actor—and I think even George Raft would agree with me.

However, Cagney’s earnestness, his relentless intensity, and his ability to structure his performances, usually building up to a climactic freak-out—all these qualities are nicely balanced out by Raft’s laconic, under-emotive coolness. Frank Ross’ sensitivity to the world and his awareness of the moral stakes of any given situation provide the catalyst for glib tough-guy Stacey to grow as a person. Ross’s energy and his righteous indignation force Stacey to actually weigh the ethical consequences of his actions for once. In this way, Cagney’s and Raft’s acting styles (and abilities) translate beautifully into their onscreen characters.

If Raft plays a more automatically charismatic character—a slang-slinging outlaw—Cagney certainly rips into the more difficult of the two lead roles. We understand his Frank Ross as a wronged man; yet, Cagney brings a strength and complexity to this risky victim role, a part that could have easily seemed like a wimp or a weakling in the hands of a less capable performer.

Frank Ross initially recalls Paul Muni’s similar role as a man incarcerated through a quirk of fate in I am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang. However, Cagney’s Ross ironically “earned” his punishment, by fighting long and hard against unscrupulous politicians who unjustly imprison him. Indeed, in the opening scenes of Each Dawn I Die, Cagney channels all of the virile aggression he displayed in his gangster roles, only turned to serve a social purpose.

Stalking through the rain in a trench coat, scaling walls into a fortress of profiteers, and smiling to himself as he watches the bad guys incriminate themselves, Cagney exudes a malevolence twisted for good, an anger born of hard-knocks and displaced onto corruption. His risk-taking star reporter doesn’t just want a story—he genuinely despises the grifters and crooked politicians he strives to unmask.

Stalking through the rain in a trench coat, scaling walls into a fortress of profiteers, and smiling to himself as he watches the bad guys incriminate themselves, Cagney exudes a malevolence twisted for good, an anger born of hard-knocks and displaced onto corruption. His risk-taking star reporter doesn’t just want a story—he genuinely despises the grifters and crooked politicians he strives to unmask.

He wants to bring them down—and he pursues their downfall with the same sort of single-minded ferocity that we tend to associate with Cagney’s less benevolent characters, like Tom Powers and Cody Jarrett. Cagney’s variation on the muckraking reporter adds a deep subtext to that stock character of the 1930s. He doesn’t just breeze through the world of racketeers looking for newspaper fodder, like many a wisecracking movie journalist. Frank Ross, who, as we later find out, rose from the slums to make something out of himself, hates criminals and exploiters of the public confidence. He hates them deeply. Personally. Intensely. Implacably.

About to spill his big scoop on the district attorney and the governor, Ross leaves his office one night, only to be seized by two ugly henchmen who hustle him into his car. Even in a moment of danger, Ross exhibits the typical Cagney moxie—he bares his teeth like a frustrated shark. We can practically hear his thoughts, saying, “Why, I oughta…!”

Unfortunately, Ross doesn’t have a chance to fight back. The baddies knock him out, force him into the driver’s seat of the car, smash a bottle of liquor, and send him out into the city traffic—to make the killing look like a drunk driving accident. Even more unfortunately, Ross wakes to discover that, although he survived the collision, three people in the other car were killed on impact. Pleading innocence, Ross nevertheless receives a harsh sentence from a judge most likely in league with the hypocritical politicos that engineered the frame-up.

GO TO JAIL. Do not pass Go, do not collect $200.

When Ross first meets ‘Hood’ Stacey, on the way to Rocky point, he’s chained to him. Unsurprisingly, given his disdain for all manner of crooks, Ross hates the kingpin on sight. Their immediate baiting dialogue offers one of the rare moments of levity in this grim movie.

Stacey: Write a piece about me when you get out, will ya? The name’s Stacey. Life sentence. I like to read my name in the papers.

Ross: If you don’t shut up, you may find it in the obituary column.

Stacey (sarcastically): Oh my goodness! Hey, deputy, willya change my seat? I don’t like to play so rough. He run over a coupla guys so he thinks he’s tough. You know how it is with the first coupla guys.

Cagney doesn’t take that talk from anybody, so, with one well-placed swing, these very different men enter into their first brawl—and win a modicum of respect for each other.

Cagney doesn’t take that talk from anybody, so, with one well-placed swing, these very different men enter into their first brawl—and win a modicum of respect for each other.

Although the unusual bromance between Raft and Cagney sustains the film, the emotional core of the movie witnesses Ross slowly transforming into a hardened, bitter man. He quickly learns to curry favor with big gangsters like Stacey. On his first day, he saves Stacey’s life by tripping a man who was about to stab him with a shiv. Soon, Ross has made the choice to look the other way when Stacey decides to murder a fellow inmate, a dirty rat called Limpy Julian.

The scene where Ross catches Stacey practicing his knife technique—but agrees to remain silent—stands out as a key moral reversal for our protagonist. “I don’t see any shiv,” He tells Stacey, with a grin, pretending not to see what’s right in front of his face. Denying physical reality, even in a metaphorical way, Ross signifies that he’s splitting from the ethics that he cherished “on the outside.”

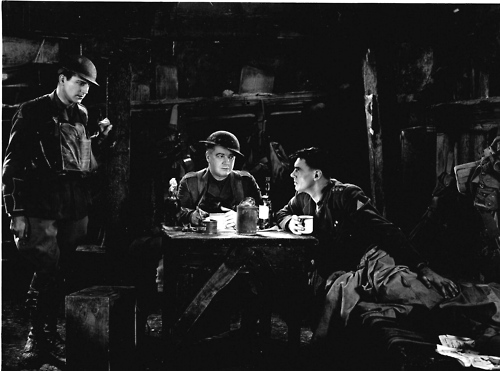

I don’t see nothing… Cagney, Raft, and shiv.

Ross’s behavior shifts to reflect a logic more germane to outlaws and gangsters, because those social menaces at least embrace their own code of honor. We perceive less justice operating in society at large than in the tightly knit circle of cons and shysters who follow their own unwritten laws of loyalty.

Ross’s eventual descent into madness proves that prisons don’t turn bad men into good ones—on the contrary, they beat an exemplary citizen into a feverish con. Seeing his basically decent comrades being abused by guards, Ross learns that Rocky Point, like the outside world, is a playground for underhanded tyrants.

In one particularly chilling scene, Pete Kassock, the sadistic head guard, accuses Ross of helping Stacey escape and proceeds to slap and punch our hero around a cell. As the camera follows Ross, being propelled around the room by the force of Pete’s blows, we the viewers can hardly believe that we’re watching Cagney passively taking this. But, then again, any protest would only equate out to more beatings.

Finally, Pete gives the nod to his men to take over the interrogation and the camera turns away, although we can still hear the dull thuds of hard punches. Whenever off-screen violence occurs in a Cagney movie, it’s usually Jimmy dishing out the beating! In this case, we the viewers feel totally helpless and shocked by the brutalizing of our protagonist, so awful that we’re not even allowed to see it. When the camera turns back, Cagney hangs limply, a broken man.

During his days in solitary confinement, in a cell quaintly nicknamed “The Hole,” the fighting spirit returns to Ross. He yells at his guards and alternately begs to be released and threatens to be worst con any of them have ever seen. Unjust punishment has turned the crime-fighter into a criminal. When Ross’ girlfriend intercedes on his behalf and the kindly warden arranges a brief respite from The Hole, we can hardly recognize the man that the guards drag into the warden’s office.

Ross sports a ratty beard and speaks with an almost mechanical rhythm, as if he’s spewing invective that he rehearsed many, many times in his head while chained in his cell. An exemplary citizen has devolved into an animal. It’s a horrific spectacle. The burden of this film’s social critique lies squarely on Cagney’s shoulders. And, boy, does he make it work.

Cagney’s performance astounded me not only with the facet of rage that he brought roaring out of the character, but also with the moments of vulnerability and tenderness. When his mother comes for a visit, bringing a basket of sweets and goodies, the ashen-faced prisoner can barely manage to eat a bite. You can tell by his halting delivery and the little catch in his throat that he’s choking back tears at every moment. When his mother eventually breaks into sobs, his whole face crumples. Those luminous eyes fold under their lids. With a nod, he lets the guard know that he can’t take his mother’s pain any more and she’s escorted away.

As Cagney walks back to the workroom, the camera tracks back in front of him and we watch him cope with his own anguish during the rare few seconds when he’s not surrounded by guards and prisoners. He wipes two tears away and steels himself back into his impassive tough-guy act.

Similarly, when Frank Ross comes up for parole only to discover that the man who’s going to make the final decision actually participated in the frame-up. Overcome with injustice and disgusted by the “sanctimonious” speeches of the parole board, Ross yells at the whole pack of them. He leaps from his seat and we’re not quite sure what he’s going to do. He shouts and screams… and then realizes that he’s killed what little chance he had of winning parole. Back-pedaling, he begins to weep, to implore the stony men before him for a second chance, for something he knows he’s not ever going to get from them.

Just as Cagney’s strength and cockiness taught America how to be strong and cocky, his grief and despair taught America how to grieve without self-pity: “You ain’t so tough,” as he sneers to himself in The Public Enemy.

In Each Dawn I Die, his wild cries of defeat howl from the heart of America’s dark side. He gives us the shadow of the American Dream: the man who rightfully clawed up from the gutter, and got wrongfully kicked back to oblivion. His passionate dismay holds all the power of a wake—a one-man wake for the freedom that was supposed to be his, but never really was.

Cagney can wring the spectator’s hearts because, through the emotional arcs he creates in his performances, his characters earn their breakdowns. His characters weep only when the situation becomes truly, utterly hopeless. Long before today’s “sensitive manhood” and overactive male tear ducts (I mean, James Bond cries these days; God help us all!), Cagney merged toughness with the occasional glimpse of raw emotional wounds and boyish tenderness.

I especially love the way he puts one caring hand to protect George Raft’s head as guns shatter a glass window above him. Orson Welles once praised Cagney for the way he could take the truth of his roles, then expand the scope of the performance to be larger than life, but no larger than truth. Never more so than in Each Dawn I Die.

Because this film was made after Joseph Breen and his reinforced Production Code, Cagney is denied the opportunity to give his performance the haunting ambiguity that we get from I am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, for instance. The movie insists that innocence and virtue will eventually be rewarded. Each Dawn I Die lacks the hard-hitting conclusion that could have made it a masterpiece.

If you’re a “square guy,” eventually the system will come through for you. That seems to be the affirmative message of Each Dawn I Die. But I don’t buy that redemptive claptrap, the stuff that the screenwriters clearly slapped onto the end to show us that the world is just. The ending of this movie should comfort us. It doesn’t. The echoes of the beatings and the miscarriages of justice and the dirty political deals still chill us to the bone.

In the world of Each Dawn I Die, a man is guilty because the right people say he is. A shiv dematerializes because one man decides to be loyal to another. Rage against criminals galvanizes into an uncontrollable criminal rage. Reality warps under the dehumanizing rhythms of days, weeks, months in jail.

And, through the magic of Cagney’s searing interpretation of Frank Ross, a happy ending doesn’t seem so happy anymore.

I didn’t end this post on such a happy note, so here’s a fun fact. According to Cagney’s autobiography, when he was president of the Screen Actors Guild, he tried to rid Hollywood of mob influences. So the mafia decided to put a hit out on him. However, lucky for Cagney, a friend of his had some pull with the gangster crowd and decided to convince his buddies to spare ol’ Jimmy. That friend was George Raft. Life imitates art, doesn’t it?

This blog post is part of the Cagney Blogathon, hosted by The Movie Projector. Cagney was a fascinating and versatile guy, so be sure to check out the other entries and learn as much as you can about this screen legend.