“I’m no Clark Gable in the matter of looks; I require a good dramatic play before my fatal charm is discernible.” —Colin Clive

“I’m no Clark Gable in the matter of looks; I require a good dramatic play before my fatal charm is discernible.” —Colin Clive

Fatal, indeed.

On this date in 1900, Clive Clive came into the world. In 1937, he died alone and unhappy in an oxygen tent, succumbing to alcohol-exacerbated tuberculosis. He didn’t stay here for long, but in some ways he never left.

He lives in a thousand imitations of his broken-reed voice, in horror movies that he hated making, in the dormant celluloid of films not available for distribution, and in my cinephiliac obsession. He always seemed to be a bundle of nerves—even beyond the diegetic gallery of tightly-wrapped characters he played, from the alcoholic Captain Stanhope to the blasphemous Dr. Frankenstein to the traumatized Stephen Orlac.

The twitchy, overblown energy of Clive’s performances, his harnessed panic, makes you somehow more aware of what the film critic Laura Mulvey has called death at 24 frames per second, the poignant passage of time as captured by the camera.

There are many things that I would like to say to Clive, but someone else pretty much wrote it all down and actually sent it to him when he was still around to read it:

“I want to thank you for the little bit of rare beauty you have given me, a real spark of something which does not exist in the world today. I am not speaking of your great acting nor the great part you brought to life so expertly. Others have done great acting before, and there have been many great parts written. I am speaking of something which, probably, was very far from the mind of the author when he wrote Journey’s End, and from your own when you acted it. Perhaps that which I saw in you exists only in my own mind and no one else would see it, or care to see. I am speaking of your achievement in bringing to life a completely heroic human being.”

This is an excerpt from a beautifully written fan letter by no less than Ayn Rand (!) who saw Clive perform in a stage revival of Journey’s End in 1934. She was herself a successful playwright at the time. Clive replied that her praise meant a lot to him. I hope that he internalized some of it. Whatever anyone may think or feel about Ayn Rand, I must admit that she seized on a key aspect of Colin Clive.

It’s ironic that Rand, who championed iron wills and inner strength, should have so admired a man whose weaknesses and insecurities destroyed him. And yet, Clive was not just a downward spiral, but an aspiration towards something higher.

It’s ironic that Rand, who championed iron wills and inner strength, should have so admired a man whose weaknesses and insecurities destroyed him. And yet, Clive was not just a downward spiral, but an aspiration towards something higher.

All of his performances have a grace and beauty to them, as if even the most loathsome characters could have been better people—should have been, but were cut off by some cruel twist of fate.

When Clive’s Dr. Frankenstein delivers his speech about clouds and stars and eternity, he becomes my personal definition of the heroic in mankind. In this case, I know exactly what Rand was on about.

Some actors have fans, and that’s just fine. Colin Clive has a cult. I wonder what he would have thought of us, the endless Googlers of his image, holding vigil over his memory. I’m not entirely sure that he would have been pleased. He may well have been a trifle freaked out.

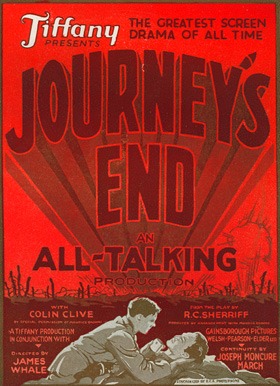

But I would like to remember him on his 113th birthday with a few words about his first film, in which he recreated his signature stage role: Captain Stanhope, a part he seemed born to play.

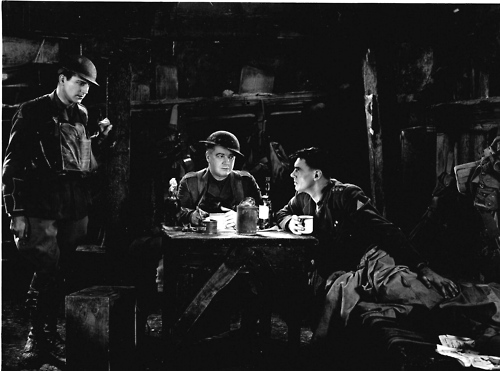

The cast of Journey’s End and James Whale listen to the radio on the set.

Directed by James Whale, Journey’s End reminds me a lot of Das Boot: quite long, claustrophobic, and character-driven. After two hours, confined almost entirely to the trench set, we feel as though we’re really in there with these damned, laughing fellows. We come recognize and cherish their foibles and mannerisms through the intimacy of the camera.

I must confess, though, the first time I saw this, I found myself disappointed by how terribly uncinematic it seems. Then again, overwhelmingly stationary shots are par for the course in an early talkie.

Whale matter-of-factly plunks us down in the trench and lets most of the action unfold in medium long shots, with the occasional significant close-up—a yucky blancmange, a box of candles, hands opening a letter. Apart from the striking chiaroscuros of a few bombardment scenes and some muddy tracking shots, we get little sense of the innovating flair James Whale clearly had for making horror jump off the screen.

However, trench warfare isn’t cinematic, is it? It’s not a sweeping crane shot. It’s not lyrical in the least. It’s creaky, stale, and soggy. Journey’s End manages to convey these qualities aptly, while still mobilizing the force of our bond with the characters to hold our attention. By about ten minutes in, we like these unfortunate chaps. We wonder which ones of them are going to die. We hope that the causalities will be minimal.

The cast works remarkably well together. David Manners, in particular, will surprise you if you’ve only seen him play juvenile romantic leads. As Raleigh, he transforms from the fresh-cheeked schoolboy soldier into a mortified, disillusioned young man. Returning from a raid in which most of the men died, Raleigh collapses onto a bed; Whale gives us a close-up of Manners who really did pull out all the stops. He looks shattered, hollow-eyed, sweaty, and broken—a far cry from his wooden pretty boy reputation.

Whale does occasionally oblige us with moments of conspicuous filmic brilliance. For instance, at the very end, when the cowardly Hibbert hesitates to join the front line, we get a shot of the doorway to the top of the trench, where a body is being carried past on a stretcher in silhouette. It borders on allegory: the doorway to death. The image shifts towards abstraction, like the famous reaper shots in Dreyer’s Vampyr. A WWI veteran himself, Whale knew how to reduce trench warfare to a bare, razor-sharp grisaille. This touch foreshadows the morbid, metaphysical resonance of Frankenstein.

Whale does occasionally oblige us with moments of conspicuous filmic brilliance. For instance, at the very end, when the cowardly Hibbert hesitates to join the front line, we get a shot of the doorway to the top of the trench, where a body is being carried past on a stretcher in silhouette. It borders on allegory: the doorway to death. The image shifts towards abstraction, like the famous reaper shots in Dreyer’s Vampyr. A WWI veteran himself, Whale knew how to reduce trench warfare to a bare, razor-sharp grisaille. This touch foreshadows the morbid, metaphysical resonance of Frankenstein.

Just as Frankenstein begins before it starts with the sounds of weeping that precede the opening images of the funeral, the deep, booming bass of exploding shells begins over the credits of Journey’s End—and keeps banging away through the film until the audience’s nerves have gone to pieces, too. Pretty astute use of sound for 1930.

Returning to our leading man, Clive became Stanhope. Or perhaps Stanhope became Clive. One can understand why Whale insisted that Clive be imported from England immediately, as no other actor would do.

Returning to our leading man, Clive became Stanhope. Or perhaps Stanhope became Clive. One can understand why Whale insisted that Clive be imported from England immediately, as no other actor would do.

This was rather unusual, that a stage actor unseasoned by cinema experience be brought thousands of miles for a single part only. Well, from the moment Clive enters the dugout set—his face half-hidden from the camera by his metal helmet, brushing briskly by, trying to drop his knapsack on his bunk, then pulling the strap off where he caught it on his shoulder with a weary tug—his every movement rings utterly true. We never feel that he’s playing for the camera, which I consider a small miracle, since he had never acted for one before.

Drunk parts are notoriously hard and perhaps Clive wasn’t faking drunk. Whatever Clive’s consumption of whisky was during production, though, Stanhope’s state of inebriation varies through so many shadings of prickly, dreamy, and cheerily garrulous that we’re watching a person shot through a prism—all the emotions that usually coexist in diluted form come through in vivid contrast. He portrays a man fractured and fragmented into pieces, pieces that some central, guiding insight is trying like mad to hold together.

The thing that nurtures Stanhope, his perspicacity, his ability to understand the point of staying strong in the midst of pointlessness, is also the thing that makes him need to numb himself out with alcohol. Like a plant which, when its growth upwards is blocked off, twists around but keeps on growing, Stanhope’s passion for life has been stunted by war into the desire to die like a man—the only option left. Part child and part old soul, Clive’s Stanhope shines with the feverish glow of the actor’s own incandescent torment.

I consider Stanhope the flip side of Clive’s Frankenstein. Both are individuals attuned to some higher significance. Stanhope delivers a marvelous speech about giddy stars and mortality that almost certainly inspired the famous monologue from Frankenstein (which was not in the shooting script, incidentally). We recognize in Stanhope, as in Frankenstein, a brutal hubris that holds everyone to a high standard—but himself to an almost impossible standard.

Perhaps most importantly, Whale shows both men (Stanhope and Frankenstein) to be rather childlike. Remember how Frankenstein, seeing Elizabeth, takes a few steps and collapses in his laboratory when his father comes for him? That moment echoes a scene in Journey’s End when, consumed by worries and heavily inebriated, Stanhope falls into his bunk and partially out of frame. His head and shoulders are off-screen as the fatherly Sergeant Osborne puts a blanket on him. It’s as if he disappeared for a moment, regressed into a place where he’s no longer trapped in the trenches, but he then calls pathetically, “Tuck me up!” In both films, Whale and Clive deliver moving depictions of men returning to helpless boyhood on the brink of exhaustion.

Perhaps most importantly, Whale shows both men (Stanhope and Frankenstein) to be rather childlike. Remember how Frankenstein, seeing Elizabeth, takes a few steps and collapses in his laboratory when his father comes for him? That moment echoes a scene in Journey’s End when, consumed by worries and heavily inebriated, Stanhope falls into his bunk and partially out of frame. His head and shoulders are off-screen as the fatherly Sergeant Osborne puts a blanket on him. It’s as if he disappeared for a moment, regressed into a place where he’s no longer trapped in the trenches, but he then calls pathetically, “Tuck me up!” In both films, Whale and Clive deliver moving depictions of men returning to helpless boyhood on the brink of exhaustion.

In one of the most moving scenes of the film, Osborne reads a letter from Raleigh, who happens to be the brother of Stanhope’s fiancée. Stanhope fears that Raleigh will unmask him as a drunkard and ruin his reputation with the girl he loves, but instead, as Osborne reads the letter, Stanhope hears nothing but kind words for his spirit and leadership. The play of emotions on Clive’s face is, as usual, extraordinary. We spot relief, yes, but also anguish, sadness, an attempt to gather his courage, as though he were facing down German machine guns. I have to commend Clive on this unique interpretation, but a very genuine one, as I believe that praise is the most humbling thing in this world. Praise frightens Stanhope more than criticism, because being a fine fellow is an ideal he has to live up to. Heroism is his curse.

Clive exuded a borderline ludicrous modesty in his interviews, claiming that anyone could have done his parts well, that it was the writing or the directing that did most of the work. This quote, from a 1932 issue of Picture Show magazine, characterizes his attitude towards fame and his obvious talent:

“It took me ten years to learn my job on the provincial stage—of course, I’m still learning now; but I’m afraid it will take me a lot longer to learn anything really worthwhile about films. The technical side is so interesting, and if ever I do master this part of making pictures I would like to produce pictures and give up acting altogether.

“You see, I’m little more than a puppet really as far as film work is concerned. The director does all the brain work. He is the man who makes the picture.”

I think that praise frightened this self-deprecating man as much as it scared Stanhope. Well, that’s too bad. I want to praise how he ruffles a dying friend’s hair, while looking away from the body in horror. I want to praise how disobligingly nasty and snappish he acts at times in the film, yet still makes us care for him. I want to praise him for “the little bit of beauty” he bequeathed to us with his performance.

Watch Journey’s End and I think you will too.

(Note: I refuse to post screenshots of this film because the print on YouTube, as well as the one on my DVD, look like they’ve been dropped in the mud at the Battle of Ypres. You can watch the full movie by clicking here, although it’s a crime against humanity that someone has not restored this magnificent film about the tragedy of war. Since no one has, I’ve decided to include a lot of publicity stills and materials in this post which I gleaned from the fantastic Tumblrs of missanthropicprinciple, sullivanstrvls, and, of course, colincliveforever. Do give them a look. They post terrific movie-related images and reflections and they have my gratitude.)

No takers? Alright then.

No takers? Alright then.

I need to rein myself in when writing about Frankenstein. God knows, I could easily concoct a series of blog posts about Colin Clive’s hair alone. So, I’ll isolate one moment that has always fascinated me and try to bring it ALIVE!

I need to rein myself in when writing about Frankenstein. God knows, I could easily concoct a series of blog posts about Colin Clive’s hair alone. So, I’ll isolate one moment that has always fascinated me and try to bring it ALIVE!